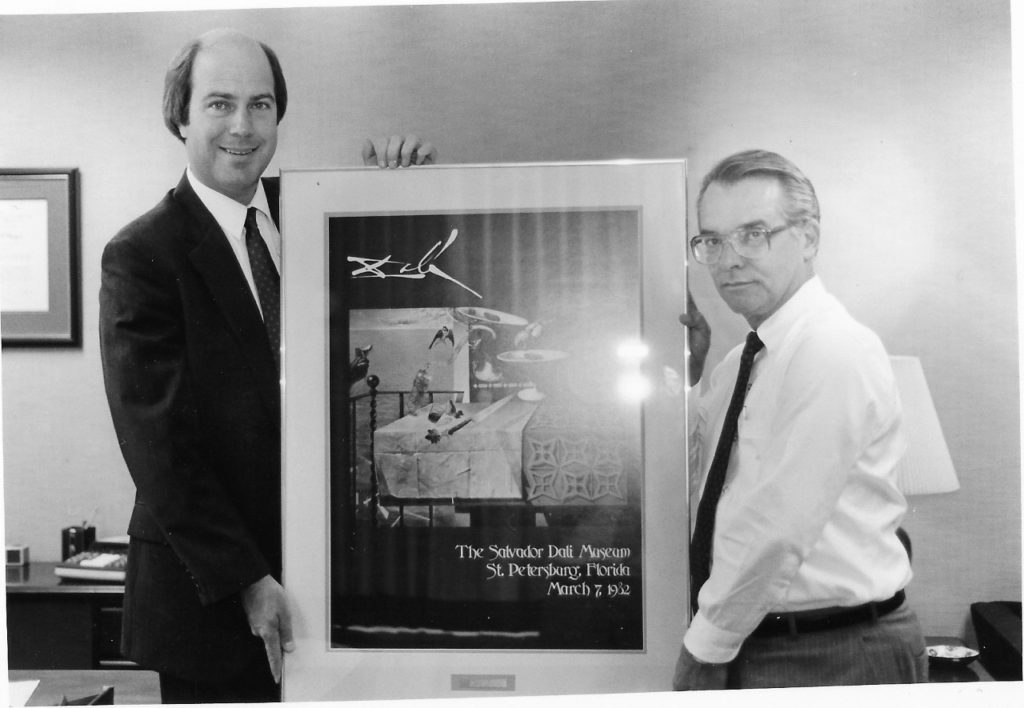

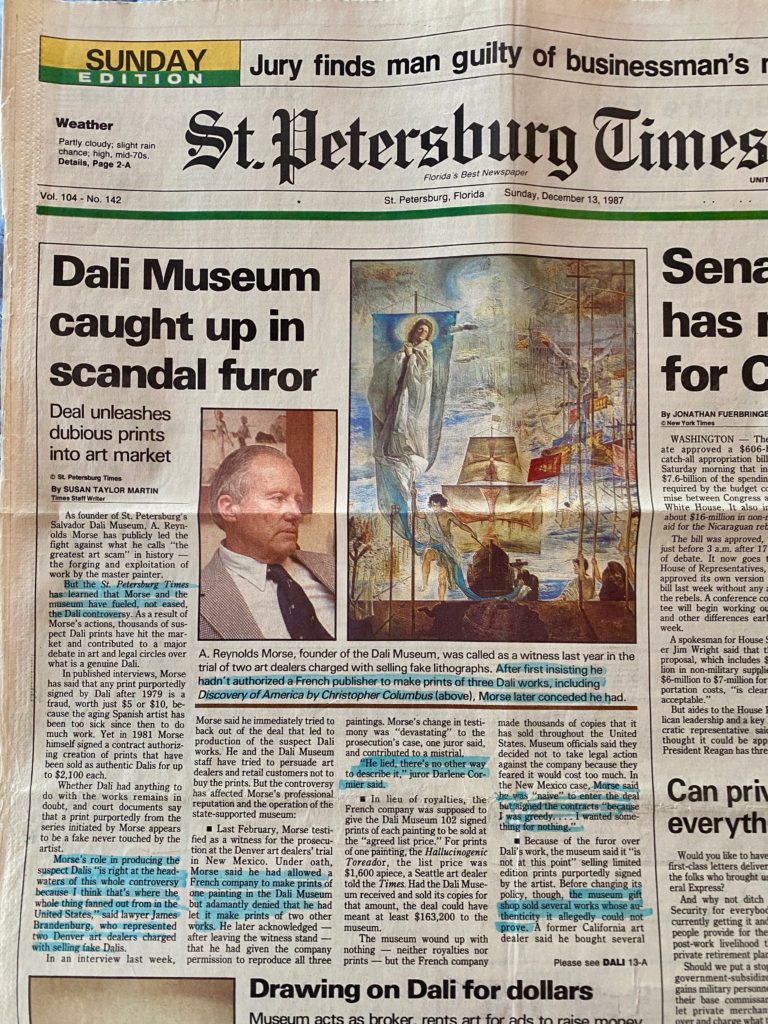

GOODBYE DALI Part 2: Print Scandal (#85): Another conflict with “The St. Petersburg Times” arose with the Dali Print Scandal and it was a huge problem. I became aware of an issue involving the Museum in the fall of 1987, when “Times” reporter Susan Taylor Martin (STM) sent me a letter with a list of questions. She included copies of three contracts signed by A. Reynolds Morse (Ren) on December 15, 1981 and stipulated into evidence in the case of State of New Mexico vs. Ronald Caven and Curt Caven and March 11, 1987.

The Dali Print Scandal is an incredibly complicated issue. To try to simplify, Ren, Michael Ward Stout, Albert Field, and Bernard Ewell were the good guys that I knew. I also believe that Ren trusted Robert Descharnes. The bad guys I was aware of were Jack West, Tom Wallace (not a Wallace from Pinellas County), and the Cavens, but there were many more.

In 1955, Field became Dalí’s official archivist upon the artist’s request. I visited Albert Field in Queens during the spring of 1987 to discuss the possibility of him leaving his archives to the Museum, in return for naming the Library in the new addition in his honor.

Albert Fields was the guest speaker at the Order of Salvador Dinner in May of 1987. His speech was going a little long and the patrons were growing restless. As I stood up to try to move things along, Albert said, “Sit down Scott. I am about to announce that I am going to be leaving my archives to the Albert Field Library in the new wing of the Dali Museum.”

Albert and Ren had a few differences over the years, as is likely to happen when two strong willed and strong minded men are dealing with the same subject, so I got the credit for the bequest. In #83, I mentioned that Ren had initially talked to me about becoming the Executive Director, but once I called Jim Martin, Ren thought I was going behind his back and things were put on hold. In February of 1987, I was hired as Director of Development. The Albert Field bequest earned my promotion to Executive Director. Albert Field died in 2003. His donation included “Landscape Near Figueras” (1910), one of Dali’s earliest known works, painted when he was about six years old. I liked Albert, and respected him immensely. He was a very dedicated man and we always got along well.

The following are only my recollections of the Dali Print scandal, verify for yourself before you buy anything. Two good books are “The Official Catalog of the Graphic Works of Salvador Dali” by Albert Field and “The Great Dali Art Fraud and Other Deceptions” by Lee Caterall.

One rule of thumb, never buy a print of lithograph of an original Dali painting. From what I learned from Ren and Albert Field, the only exception is “Lincoln in Dalivision”. Also, never buy a signed Dali print or lithograph that includes a Certificate Of Authenticity signed by Dali. It is extremely doubtful that Dali would waste his signature on one.

There was a huge amount of money to be made selling fake prints or lithographs supposedly produced and signed by famous artists. Take a $10 sheet of high quality art paper, spent another $10 on reproducing a high quality image, then forge a signature. For extra inducement, include a CERTIFICATE Of AUTHENTICITY with a forged signature.

The trick is to get someone to believe this $20 sheet of paper is worth $3,000, when in reality it is worth no more than a high quality poster. Never underestimate the skill of a good conman. A slick talker in a fancy Gallery at a tourist destination could rake in a lot of money from unsuspecting dupes. The Gallery would almost certainly have legitimate Dali prints for sale, and perhaps an original Dali painting or water color on display, to add to the deception.

The conman’s spiel may go like this; “Dali is in bad health. You know what happens when a famous artist dies? The prices sky rocket. This is your opportunity to invest before that happens.” Or, “Sadly Dali is dead. But that creates an opportunity for a smart investor. No more of these valuable lithographs are being made. The prices are going through the roof. In 10 years a few of these could pay for your daughter’s college education.” And, “Have another Piña colada. Of course we take American Express.”

Dali was to a degree responsible for the mess, due to what some describe as sloppy business practices or just plain greed. He paid his personal assistants inadequately and allowed them to take a piece of the profits from deals they put together. John Peter Moore and Enrique Sabater persuaded Dali to pre-sign blank sheets that would be used in the printing process of authorized lithographs. “With aides at each elbow, one shoving the paper in front of Dalí and the other pulling the signed sheet onto another stack,” wrote Lee Catterall, “it was claimed that Dalí could sign as many as 1,800 sheets an hour…”

As word of sheets pre-signed by Dali spread, so did the temptation to forge his signature. In 1974, at a routine customs stop, French police found 40,000 sheets of paper, all with nothing but the signature of Salvador Dali. Since there was no documentation that these sheets were to be used for authorized lithographs, they were presumed to be false. This was just one shipment, but there must have been many more and it gives you an idea of the magnitude of the problem.

Further confusing the situation, Dali refused to honor an agreement to produce 78 tarot card illustrations and between 1976 and 1977, signed 17,500 blank sheets of paper to settle a lawsuit brought by Lyle Stuart.

Between 1980 and 1989, Dalí was seen in public only once. “So in the 1980s you have the artist alive, but not around to cause trouble with what the publishers and forgers were doing,” wrote Bernard Ewell, a well respected art appraiser. “It was basically a perfect storm: There was a market, there were lots of yuppies with disposable income, and nobody knew anything. Rumor really just drove everything.”

With the crooks turning out fake Dali prints and lithographs by the thousands, and Dali not around to verify which were real, luckily there were the good guys. The crooks, however had the money and the incentive to try to discredit the good guys.

The three contracts Ren signed in1981 were enough to convince STM that she was on to a big story. To put it simply, Ren got fast talked by a conman who knew how to play on his emotions. Jean-Paul Delcourt, from Paris, came to see Ren on a Saturday in December,1981, supposedly at Dali’s request. Dali’s health was declining, but he wanted to help his good friend as he was about to open the Salvador Dali Museum in the United States.

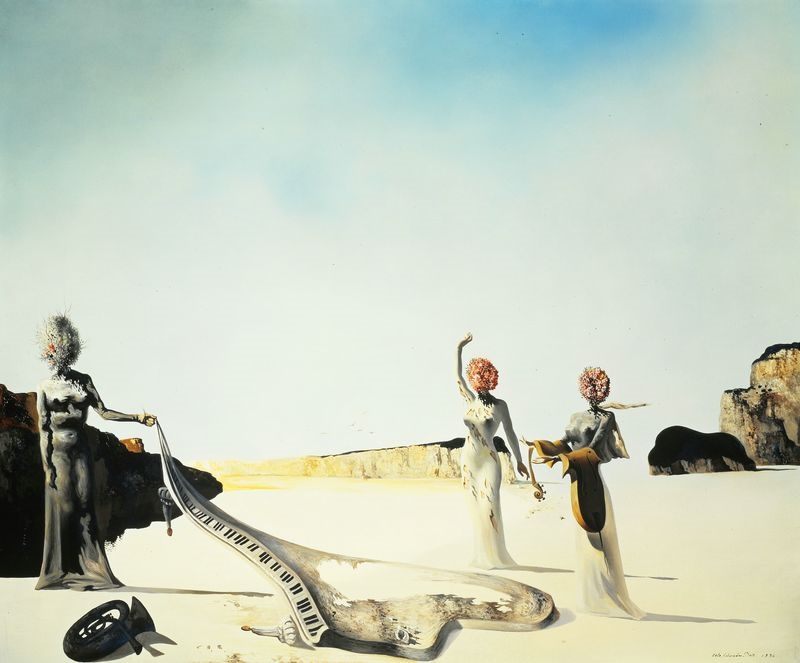

Dali had suggested that Delcourt work with Ren to make lithographs (zinc plate method) from three of Dali’s favorite paintings in the Museum: “The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus”; “The Hallucinogenic Toreador; and “The Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Hands the Skins of an Orchestra”.

Ren told me he was flattered by Dali’s attention and at the time thought that having high quality limited edition lithographs to sell in Museum would be a good idea. On Monday Ren called Michael Ward Stout, an attorney specializing in intellectual property rights who represented Dali in the United States. Over the years Ren and Michael had become good friends and Ren often sought his advice. It was clear that Ren had been tricked. Michael said Delcourt was a crook who had no connection with Dali. Michael immediately sent letter voiding the contracts because of fraud. But the damage was done. Even though voided, the contracts were out there.

The crooks came to St. Petersburg, opened a gallery, and made every attempt possible to intimidate Ren and damage his credibility as a witness in future criminal and civil trials over Dali art fraud. They armed STM, not only with the three contracts, but everything they could think of to confuse the situation. For instance, why was the museum selling any lithographs at all. Even ones Ren and Albert said were authentic?

In my opinion, Ren was embarrassed and tried to avoid the situation. He refused to talk with STM, and this convinced her even more that she was on to a story. I always felt if we had talked to STM in the beginning, and told her everything, we could have diffused the situation. But we didn’t, and things came to a head one Sunday.

Mike Wallace had interviewed Salvador Dali in 1958, the 30 minute interview was classic. In 1987 he came to St. Petersburg to showcase the one man, Salvador Dali Museum for “60 Minutes”. He had been impressed, was very complimentary, and all went well – until the Sunday the piece was to air. I walked out that morning to get the paper, and there was Mr. Morse, above the fold, on the front page of the Sunday “Times”.

STM must have thought “60 Minutes” was going to do a hatched job, and she wanted to chop us up first. Here were all of the crooks’ allegations against Ren in three articles by STM, spreading from the front page to a 1/4 page on page 12 and a full page on page 13. In the center of page 13 in a one column wide and 11 line long box was the totally false statement:

“60 Minutes” to air Dali segment today

Tonight at 7 on Ch. 13, CBS’ “60 Minutes” plans to broadcast a segment looking at the controversy over false Dali prints.

I don’t know where STM got that information, or if she just assumed she was the type of quality reporter “60 Minutes” would hire and they were obviously going to do the same kind of story she was writing. She couldn’t have been more wrong, or at least any more wrong than she was about Ren. See how easy it is to get mad, and then civil discourse goes out the window. I never intended to insult STM, but seeing that misinformation made me want to give it a shot. The “60 Minutes” segment could not have been more flattering.

The damage by STM had been done. Ren wouldn’t talk to her, and he specifically told me not to talk with anyone from the “Times.” That was a little hard to do when their Comptroller, John O’Hearn, was on the Board, Jake Lake had been involved in bringing the Morses to St. Petersburg, the “Times” was our biggest donor after the Morses, and Andy Barnes was getting involved. Thereafter, any more bad publicity from STM was clearly my fault, “I told you not to talk to them.”

Jim Healey did all he could, but the situation kept deteriorating. I met with Jack Lake and he said he thought I was handling things the best way possible. John O’Hearn resigned from the Board in June of 1988. Things finally died down in 1989 after the law suits played out and the crooks were either forced out of business or at least quit selling obviously fake Dalis.

When the dust settled, the damage was still evident. Ren and Eleanor were hurt again – their thanks for giving the City of St. Petersburg the biggest gift in its history.