GOODBYE DALI Part 4: The Dali Jewels (#87A): In June 1987, Linda and I took trip to New York. It was on business for the Dali Museum, but we worked in a lot of fun.

Mohawk Carpets had commissioned Salvador Dali to make several gouache paintings as potential carpet designs. Ren had been in negotiations with Carlos Alemany to purchase three that he owned for $150,000. I was to visit Carlos at his office in the St. Regis Hotel, inspect the gouaches, and if they were in good condition, deliver a certified check, and arrange for shipment to the Dali Museum.

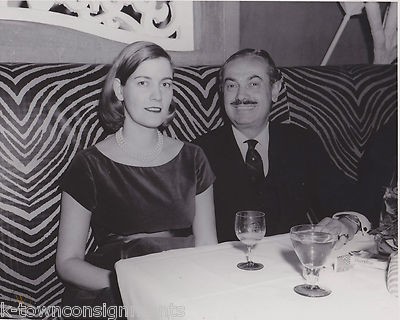

The Argentina-born Carlos Alemany had made the Dali Jewels, and was a gentleman unlike any I had ever encountered. A small man with a mustache, he was impeccably dressed. He wore spats, carried a gold headed cane, and sported a derby hat. His office walls were adorned with photos of him with famous actresses. Gina Lollobrigida, Claudia Cardinale, Brigitte Bardot, and Sofia Loren seemed to be his favorites.

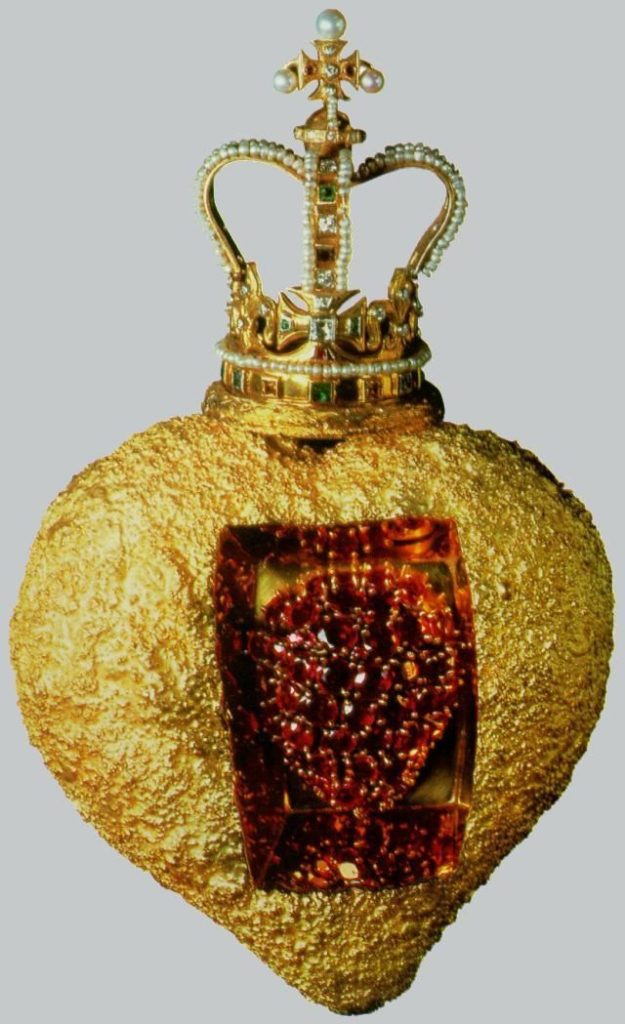

The Dali gouaches were in fine condition, and after we concluded our business he seemed to have plenty of time to talk. He told me about making the Dali Jewels and how Dali had almost caused him to go bankrupt. He had approached Dali in the late 1940s and Dali agreed to make three 3 X 5 sketches for $500 each. Carlos thought he didn’t have anything to lose, a large Dali sketch was certainly worth $500.

Carlos said he should have know Dali was going to be difficult to work with when he got the sketches. They were very small, 3” X 5”. He explained that normally when jewelry is made, the material, gold, diamonds, etc., make up the majority go the cost. The Dali jewels were so intricate that labor made up the majority of the cost. If he couldn’t sell the pieces as jewelry, and had to sell them for materials, he would lose a fortune.

At this point Carlos gave me a manuscript he had written about working Dali. He said he did not want the manuscript published until both he and Dali were dead. He worked at his desk, while I read and picked up with the story.

When the first set of 22 pieces of jewelry were finished, he and Dali planned the opening show. Dali insisted on handling the invitations, he wanted only the most important people to attend. Dali insisted on Wells Fargo guards with guns, “It is very important that they have pistols, to show how valuable are the Dali Jewels.” Dali also insisted on Dom Perignon champagne. Carlos was so broke by then, he had put everything he had into the jewels, that he had to borrow the money for the champagne from his secretary.

The day before the opening he had received no RSVPs. The morning of the show Dali called. He had decided he shouldn’t come, because if he did he would overshadow the jewels, “Everyone will just want to see Dali.” When Carlos told Dali that there were no RSVPs, Dali told him not to worry, “The famous people do not bother to RSVP. Everyone will be there.” That night, no one came to the opening. Carlos, his secretary, and the two Wells Fargo guards sat waiting and drinking Dom Perignon, but no body came.

Carlos told me that fortunately he was able to sell the entire collection to an American millionaire, but he barely broke even.

There was one absolutely outrageous story in the book that I have to tell you. Carlos swore to me that the story was true. A Maharaja had given Dali a large ruby and wanted him to design a special setting for it. Carlos was to make the piece of jewelry. The Maharaja had come to see Carlos, and explained that he was returning to India in a week and wanted to take the ruby with him. Carlos called Dali, explained the situation, and Dali told him to come to his hotel in the morning.

When Carlos arrived, Dali was with a very attractive woman in a long robe. Dali took the ruby and led the woman into the bedroom, leaving the door opened. Carlos sat on a couch, but eventually his curiosity got the better of him. He got up and looked in the bedroom. The model was naked, sitting on the bed with her legs spread. Dali was on his knees, combing her pubic hair.

Carlos hurried back to the couch and waited. About 20 minutes later he heard a scream. The model came running out of the bedroom, pulling on her robe. There was red running down one leg. A few minutes later Dali walked out and looked at Carlos, “You should have told me it was wax. If I had know, I never would have put it there.”

I told Carlos that I had been talking with Albert Field about the possibility of Albert leaving his archives to the Museum, adding that if Carlos entrusted the manuscript to us, we would see that it was published on his death. He was noncommittal, perhaps the owner of the Dali Jewels would want it. In 1958 the Owen Cheatham Foundation bought the jewels from the original buyer. In 1981 the collection was acquired by a Saudi multimillionaire, and later by three Japanese entities, the last of which agreed to sell the collection to the Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation. The Dali Jewels now have a permanent home in the Dali Theatre and Museum in Figueres, Spain.

When I returned to the Museum on Monday, I gave Ren an update on the events in New York, including the possibility of obtaining Aemany’s manuscript. He said he would take care of Alemany. In my research today, I found no mention of Carlos Alemany’s manuscript. I hope it hasn’t been lost forever.

The Dali Mohawk Carpet gouaches arrived at the Museum later that week. Joan Kropf and I unpacked them in the library to make sure there had been no damage in shipment. They were fine. A few of the staff came to take a look. When Ren came to the Museum the new day, I caught hell for showing the gouaches to the staff.

Another problem arose a few years later when Bernard Ewell was appraising part of the collection for tax purposes for the Morses. Even though I knew nothing about the appraisal, I was blamed for having Ewell appraise the gouaches, which were appraised at $35,000. I pointed out that we had paid $50,000 and said we should talk to Ewell about the figure. Ren though I was accessing him of overpaying, said I was a worry wart, and to forget about it. When I brought it up again he said I was acting like an old lady.

I knew the pieces we worth what we paid, but if Susan Taylor Martin (STM) found out, she would make it into a big deal. I had no choice but to go to the President of the Board of Directors, hoping he would tell me not to worry. Just the opposite, “You can’t leave it like that.” I had a few more tense talks with Ren. “We got a good deal. Carlos wanted $160,000, but you got him to accept $150,000. That was a great price, but if STM gets ahold of this, she’ll make it look like we paid too much.”

Finally, Ren agreed I could call Ewell. The next day I was with Ren when Bernard called. I handed Ren a note, “Please ask him about the gouaches.” Ren said, “Scott is worried to death because we paid $50,000 each for the gouaches and you only appraised them at $35,000.” Bernard said that what we paid established the price and he would send a new appraisal at $50,000 each that afternoon.

Sometimes doing the right thing can be tough, but if you don’t deal with the situation it can come back to haunt you. Take what happened with the three contracts Ren signed in 1981. They were revoked, but Ren wouldn’t talk to STM about them (See #85) and it turned into a nightmare.